Design is the Problem

Review by David Sherwin

“Would you like a paper or plastic bag for your groceries?”

Seems like a simple question, doesn’t it? Paper should be a better choice, because it will biodegrade. Plastic will go on forever in landfills and choke our oceans.

Well, my answer isn’t very well informed. There are major trade-offs in the consumption, production (and related pollution), and recycling opportunities for every seemingly simple decision that we make throughout our lives, both as consumers and as designers.

And this is the crux of Nathan Shedroff’s useful book, Design Is the Problem: The Future of Design Must be Sustainable (Amazon: US|UK). Within its pages sits a fully realized schema of the minutia that working designers and students need to internalize in order to start making more educated decisions regarding the sustainability of their client and personal projects. Being mindful about sustainability—both in the products and services we design, and in the decisions we make as consumers and creators in an ever-evolving economy—can be an astoundingly complex and time-consuming undertaking.

Commenting on the paper vs. plastic debate, Shedroff says:

“One has to be better than the other, right? This is one of the problems with sustainability. The issues are so complex and interconnected that even the experts are having difficulty coming to conclusions. Customers simply want to know which is the better product to buy. Most are, overwhelmingly, interested in buying products that support their values. However, we can’t give them the information they desire because we don’t yet know it ourselves… There may be an even better answer, though. How about no bag? Or a reusable bag?”

This is one of the benefits of espousing a “systems thinking” mindset, which is critical to considering issues of sustainability. This mode of thinking allows us to disassemble the everyday assumptions that our clients provide us and consider every aspect of the design process in thorough, considered detail:

“Design that is about appearance, or margins, or offerings and market segments, and not about real people—their needs, abilities, desires, emotions, and so on—that’s the design that is the problem. The design that is about systems solutions, intent, appropriate and knowledgeable integration of people, planet, and profit, and the design that, above all, cares about customers as people and not merely consumers—that’s the design that can lead to healthy, sustainable solutions.”

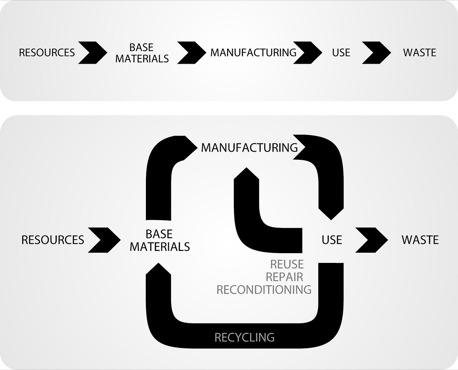

Design Is the Problem is broken into multiple sections: an introduction to the concept of sustainability, a high-level primer for the reduction of material and resource use, reuse, recycling, restoring, and the processes we may take as designers to measure the impacts of our design decisions.

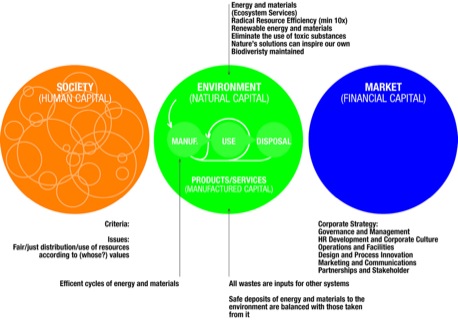

Over the course of the text, he also provides a guided tour through a wide range of sustainability frameworks that have been developed over past decades, such as Natural Capitalism, Cradle to Cradle, Biomimicry, Life Cycle Analysis, Social Return on Investment, and many others. He not only catalogues the strengths and weaknesses of each—with clear-eyed regard to how they consider address environmental, social, and financial issues—but he also shows how they overlap, and provides a summary framework that you can adapt for your own use.

These frameworks are useful as a way to structure your thinking about how you approach your everyday work and your client’s (often unarticulated) needs. They also help you balance the inevitable trade-offs you’ll have to make. Shedroff himself is quick to note, quite early in his book, that we should be careful not to aspire to an impossible ideal:

“You won’t ever create a perfect solution. Ever. You will have to be satisfied with creating better solutions along the way—each update, hopefully, better than the rest, and potentially no solution ever reaching your ideal vision of ‘how it should be done.’ Every design solution is a compromise of some kind, bowing to structural, financial, or environmental realities, and conforming to customer, market, or client desires. That’s the nature of design. If you’re creating real solutions for real people, the market will probably not yet be ready for the ultimate solution you envision.”

Shedroff is careful to discuss the best- and worst-case tradeoffs with each design specification choice that you make. In a section about substitution, he notes that the use of PVC should be avoided whenever possible—but also acknowledges that if it can’t be replaced with a non-plastic material, there are a range of other plastics that, while not recyclable, will have a lower impact.

Where this book really shines is in the eloquence of its language, its fluid ease in itemizing the thorny details of everything from production methods to societal trends invented by corporations such as planned obsolescence and retail therapy, and the case studies illustrating most sections. (I appreciated the one about Apple’s invisible commitment to reducing materials use in practically every single design they make.) There is an immense amount of data jam-packed into this volume.

Where this book stumbles a little, for me, is in how Shedroff’s discussions of making meaning—the subject of a whole other book that he’s written—is woven through the narrative. As I was reading through the text, paragraphs such as these would often pop out:

“…products that are meaningful (that resonate with our values, emotions, and meanings) are often the most satisfying and durable of all. To whatever extent you can develop products and services that connect deeply with customers, the likelihood that your customers will keep these products longer increases dramatically.”

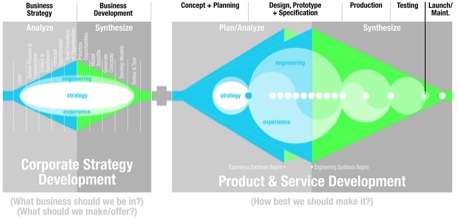

Perhaps Shedroff is worried that we may place sustainability considerations at a fixed point in the design process, as opposed to grounding every design that we make in more holistic considerations regarding the impact of every design decision throughout the entire process (including our client’s business strategies). The sustainability discussion definitely lives at the highest levels of our consideration, including the maximization of usability, meaning, and accessibility in products and services that we create, both online and offline. He notes this in this book.

However, there was some intriguing debate at the Interaction 10 conference after Nathan’s keynote speech, in which he spent a great deal of energy talking about creating meaning for people through our design efforts, how this was possible through the adept manipulation that we can exercise thoughtfully via our design skills, and that concerns of sustainability should be reflected in these meaning-making decisions. In doing so, we can hopefully create a culture where consumption is reduced and our resources are used more effectively. “Those who engage the world in meaningful ways don’t look to products and services so much to satisfy their core meanings,” he says in this book.

This tension between the actions of the designer and the never-ending flow of our culture creates a sort of circular, “cart before the horse” argument that provides an interesting tension through these pages. Design can influence how our culture considers the value of sustainability—embedded in the products and services that swirl around us—but our consumption-focused, marketing-centric culture will also need to (de)volve to allow that shift.

So, who’s going to act first to effect this change: the designer, the marketer, or the consumer? Shedroff says we are, and by transcending our stated client problems and think about the (often outdated) systems they persist within:

“…the last think our clients and companies want to hear when they engage us is that ‘we need to back up here and examine whether the whole system needs to be readdressed’ or ‘this is really a cultural issue, and it’s not solvable by simply making a new product.'”

Yet this is exactly what we should be working towards as designers: thinking beyond artifacts, and into the ways that our culture functions as an complex, interconnected system. However, working to make more sustainable design decisions requires you to set boundaries or interests to frame your sustainability argument; otherwise, you could spend forever tracing the interconnections between various issues within a system that you want to influence. Part of being successful in making decisions regarding sustainability is in broad awareness of the potential issues and judicious research in the areas of deepest impact.

The end of the book covers the actual production and marketing of your product or service. How do you go just far enough down the rabbit hole in considering these issues for your clients? How do you properly market and advertise these more sustainable products and services? Measure their impact? The final sections of the book consider these questions.

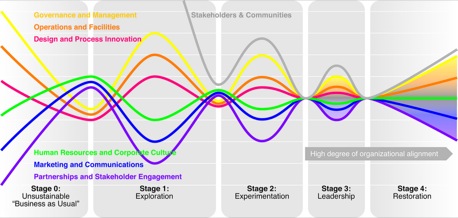

Reading through this from cover to cover, a layperson or student designer may not be able to grasp how all of this data can be applied to your daily, professional practice. Shedroff provides plenty of frameworks, such as this one, which seems more useful for larger-scale design organizations and corporations to adapt for their use:

The “super summary” in the book’s appendix is a great checklist that designers can begin using right away as a punch-list.

I definitely think this book is worth owning, either as a (DRM-free) PDF or as an (ulp) tangible book on your bookshelf. It’s a strong starting point regarding the subject of sustainability for any design professional, providing an initial frame for you to structure your thinking regarding this immensely complex subject.

For those who are currently responsible for planning, researching, and crafting tangible products or services, this book will prove as an invaluable desk reference on how to incorporate systems thinking and considerations of sustainability into their project’s business processes. I know that I will be pulling this book down frequently from my (virtual) bookshelf for many years to come.

(As a side note: A good nonfiction book to read alongside Shedroff’s book is The World without Us by Alan Weisman, which helps to visualize many of the sustainability issues included in Design Is the Problem—and in a manner that may hit home more strongly on a gut level.)

Design Is the Problem: The Future of Design Must be Sustainable is available from Rosenfeld Media as a physical book or digital (PDF) edition. Use the code DROB for a 15% discount. You can also order it from Amazon US and Amazon UK or The Designer’s Review of Books Amazon store (which helps us keep the site running).

All review images used under CC licence from Rosenfeld Media and available on Flickr

About the Reviewer

David Sherwin is a Senior Interaction Designer at frog design in Seattle, WA. He maintains the blog ChangeOrder: Business + Process of Design. His first book, Creative Workshop: 80 Challenges to Sharpen Your Design Skills, will be out in November 2010 from HOW Design Press.