Designing Design

“Creativity is to discover a question that has never been asked. If one brings up an idiosyncratic question, the answer he gives will necessarily be unique as well.” – Kenya Hara, Designing Design.

This philosophy is the thread that runs through the entire text of Kenya Hara’s deep and thoughtful book, Designing Design (Amazon: US

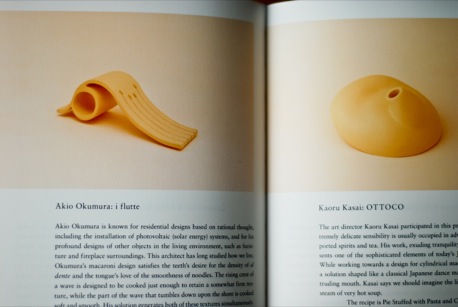

Macaroni? At first this feels like and almost insulting task, a practical joke. Wouldn’t it be hilarious to bring these egotistical designers of monumental buildings down a peg to a more everyday level? And whilst there is definitely a hint of playfulness in Hara’s brief it soon becomes clear that he gives it out of earnest curiosity.

(Click to enlarge)

Such a simple brief gives rise to the insightful analysis of structure and form in design from both Hara and the architects. When Hara visited a pasta making factory himself, he was stunned by the complexity of the design and market constraints that govern its manufacture, which is what made his simple brief so compelling. It also showed that even these great design minds of architecture had trouble competing with pasta makers and home cooks making tiny iterations over many generations to find the optimum shape that is used the world over.

Designing the question is designing design and throughout the book each section tackles this from a different angle through a series of essays and examples of projects. It feels as if Hara is constantly trying to find a way to express his particular way of seeing the world in words. I wrote on Playpen that Hara starts his preface saying, “verbalizing design is another act of design. I realised this while writing this book.” Yet, as engaging as Designing Design is, words are slippery, especially in translation (and the translation, as far as I can tell without reading Japanese, is very good). Looking at his design work says so much more than words can.

(Click to enlarge)

Hara spends some time defining design, especially in contrast to art. Somewhat surprisingly his initial stab brings him little further than the discussion most design students have sometime during their training:

“Art is an expression of an individual’s will to society at large, one whose origin is very much of a personal nature […] Design, on the other hand, is basically not self-expression. Instead it originates in society. The essence of design lies in the process of discovering a problem shared by many people and trying to solve it.”

The “process of discovering a problem” is the secret ingredient that makes and he expresses it better in the opening quote: “Creativity is to discover a question that has never been asked.”

As designers we tend to learn that our job is to solve problems creatively or, perhaps, solve creative problems, though the latter always feels a little superficial. From our student days to our commercial lives, those problems are often presented to us by others. Professors and clients tell us the brief and we set to work, much in the same way as Hara set the architects the macaroni brief.

The oft-cited cliché that the first thing to do is “tear up the brief” feels somewhat agressive in comparison. Hara’s approach is subtler, like being able to step inside a mirror and see yourself genuinely as a stranger.

(Click to enlarge)

As far as I am aware, the book comprises a series of writings spanning several years and it feels like we see Hara growing and changing as a designer. Society and the designer’s role in it becomes a more important question for Hara as the chapters roll past.

“Design is like the fruit of a tree. In product design vehicles and refrigerators are the fruit. Design functions from the perspective of how to produce good fruit. If you look a the tree from some distance, you see next the tree that bears the fruit and then the soil in which the tree stands. Important to the whole process of creating good fruit is the condition of the soil.”

When he tackles issues such as sustainability and technology, Hara ponders what might have happened had the Industrial Revolution not have come out of Europe and the affect that has had on Japanese design culture. He expresses a sadness of the cultural importation of Western design ideals at the cost of traditional Japanese design thinking. The lack of originality this signifies disturbs him, even while the West imports Japanese and Asian design back again. There is a kind of yearning in Hara’s writing for Japanese creative culture to find its soul again despite, or perhaps because of, neighbouring China’s growth.

“From now on, and for some time, Japan will be standing right beside, and observing, a bustling China in the verge of an economic boom. It’s like looking upon a gigantic shopping centre newly built in the neighbouring town.”

From the bustle of China’s trade to the hustle of electronic information, Hara strives, Zen-like for balance and quietness in the midst of the seemingly unstoppable force of technological advancement.

“In a world in which the motive force is the desire to get the jump on the next person, to reap the wealth computer technology is expected to yield, people have no time to leisurely enjoy the actual benefits and treasures already available, and in leaning so far forward in anticipation of the possibilities, they’ve lost their balance and are in a highly unstable situation, barely managing to stay upright as they fall forward into their next step.”

Whilst he is no technophobe, Hara worries that our increased access to knowledge is an illusion:

“Against the backdrop of the evolution of media and its powerful gathering of news material and data, all of the world’s happenings are trimmed like a lawn by a mower, with fragments of information flying about from place to place through the media as grass flies through the air. These broken pieces of information adhere to our tofu-like brain like spices sprinkled so thickly that they obscure the entire surface. For a moment, this makes us think we’re quite knowledgeable, but information tacked on the surface of the brain doesn’t amount to much when you add it all together.”

This philosophy of balance plays a part in his views on sustainability, obviously, but is also deeply embedded in the MUJI brand, for whom Hara is the Art Director. There is a large section on MUJI and the no-brand philosophy behind it, part of which is about not designing for desire. It is not that objects should not be well-designed or aesthetically pleasing, but that this isn’t the end point. Hara’s aim with MUJI to design for adequacy.

(Click to enlarge)

On the surface this sounds, to Western ears, as striving for mediocrity. (I imagine this sounds particularly so to North Americans – correct me if I’m wrong). The nearest Western brand with a similar philosophy is maybe IKEA, but not quite. Hidden in this philosophy of adequacy is an expression of balance, of consuming only was is required, not more not less, of not designing newer versions for the sake of technological advancement. It’s not about the next big thing, it’s about the next small thing.

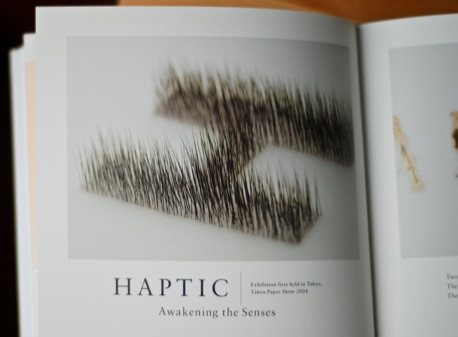

In Eye magazine’s The Form of the Book series, I described the physical production of Designing Design as reflecting the balance of style and content, action and non-action. It is one of my favourite design books in terms of its physicality. It has a stillness and a haptic sensuousness that helps you focus on the content whilst experiencing Hara’s design approach at the same time:

“If putting as many words as come into your head in some place that’s convenient and easy to access is your goal, you can house them on the web or on something like CD. But here I’ve chosen the medium called a book. That’s because I want to hand it to people as an object with a resistant weight.”

“If electronic media is reckoned a practical tool for information conveyance, books are information sculpture; from now on, books will probably be judged according to how well they awaken this materiality, because the decision to create a book at all will be based on a definite choice of paper as the medium.”

(Click to enlarge)

This physical gravitas is hard to resist and there is a danger of taking everything Hara writes as gospel because of it. The section on MUJI I found particularly tricky in this regard. Despite some of the fine ideas it contains, for me it reads too much like a MUJI brand manifesto – “everything, yet nothing” – with little critique. And at no point does Hara face the problem that a no-brand brand is, ouf course, a brand however hard they skirt the issue. It feels like he is continually fighting to keep MUJI out of the gravitational pull of its own brown, yet it is inevitable that everything they do eventually gets sucked into the centre to form planet MUJI.

Hara is ultimately a modernist at heart, albeit with a particular Japanese perspective in which the relationship between form and function is less important than balance of the whole. Even his pithy dressing down of “The Prank of Postmodernism” is more a question of vulgar over-balance than anything else:

“On the brink of the explosive spread of personal computers, we were bound to head into the infancy of yet another new economic culture, but on the eve of that birth, for just a bit, design strayed into a bizarre labyrinth.

“[P]ostmodernism cannot be seen as a turning point in design history. It was just a fleeting commotion that occurred during the hand-off of the concept of modernism from one generation to the next. If we look carefully, we can even see postmodernism as an event symbolizing the aging of the generation of designers that sustained modernism.

“From the trends in the plastic arts, it is clear that postmodernism was a small, manipulated system of icons and something of a fad. Photos of people in old-fashioned clothes of any past era make us laugh because of the strangeness of an entire society’s participation in this empty agreement called fashion. Viewed from the 21st century, postmodernism makes us laugh for the same reason.”

As a student of the early 90s lectured to by Professors beguiled by postmodernism, themselves taught by the ‘68 generation of post-structuralists , I have great sympathy with this view. No doubt other readers will take Hara to task over his treatment of postmodernism (feel free to fire away in the comments).

(Click to enlarge)

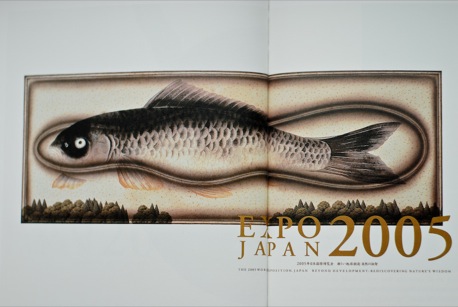

Given the beauty of much of his work and seeming ease with which Hara is able to train his design eye to the world, it was somewhat of a relief to read about the failure of his plans for the AICHI EXPO 2005. In truth, this was not a failure of the design elements so much as a failure to manage the public’s expectations and fears. The expo was intended to be set in an area of beautiful forest. The intention was really to hold the expo in the forest, not clear it, but the public’s prior experience of expos clearing land started a protest which eventually killed off Hara’s poetic plans and they were mutated into something else.

Out of the ashes of this experience, Hara resolved to use the active nature of design to create new approaches, not just use design to protest:

“[E]ven after experiencing such a setback, I have come to think anew that as a designer, I would like to take part in conscious projects with clear intentions, even if they involve aspects that don’t go so well. I am not interested in creating messages that stand against something, like messages against nuclear development, or anti-war messages; design functions as part of a planning process.”

Lars Müller, the book’s publisher, said to Hara, “Monographs belong to the last decade. You must not be a subject, but an author.” Wise advice and Designing Design is certainly no superficial monograph. The questions Hara raises, the approaches he takes to finding those questions and the depth of his knowledge make it undoubtably an essential read for any designer. His reading of design history from a Japanese perspective is also something that many Western designers might not know.

If you are a designer involved in the making of objects, it is certainly up there with Papanek’s _Design for the Real World

You can support The Designer’s Review of Books by buying Designing Design from Amazon (US